During President Trump’s term in the White House, a portrait of our seventh president, General Andrew Jackson, adorned the Oval Office. Despite much bellyaching from the propagandists in the mainstream media highlighting Jackson’s legitimate faults and unjust decisions, Trump felt a historic connection to Jackson as a president who railed against the political elites of his day and set out about forging a path to a new political future and rebirth of liberty.

Newt Gingrich, Steve Bannon, and others have referenced Trump’s Jacksonian qualities. Bannon, prior to Trump taking office, said “Like Jackson’s populism, we’re going to build an entirely new political movement.” Bannon was, of course, referring to the America First movement that is now going head-to-head against bureaucratic statism as carried by the establishment Democrat and Republican parties.

In seeking to discredit Trump’s political resemblance to Jackson, media sources often cite Trump’s lack of military service, or the fact that Jackson had held office prior to winning the presidency (he was Tennessee’s first congressman), whereas Trump had not. Seeking to bash Trump, they question if his decision to display Jackson’s likeness stems from a subliminal, or even active, approval of policies such as Indian removal or slavery.

One notable difference between the two that is of interest to me is that Jackson’s presidency (1829-1837) took place during a Third Turning, the span of twenty years within the generational saeculum known as the unraveling period, while Trump’s term took place in our current period, the Fourth Turning, or crisis period. Jackson faced a secession crisis at the end of his first term and spent much of his presidency, when he wasn’t battling the banks and the political establishment, trying to balance national sentiment regarding slavery, or dealing with other contentious issues such as the aforementioned Indian removal, westward expansion, and the deepening tensions between north and south over a variety of other issues.

Trump highlighted Jackson during his term, not knowing what would befall him in the ill-fated, corrupt 2020 election. What I will lay out in the balance of this article is how Trump is much more like Andrew Jackson than we once realized, especially now that the 2020 election has unfolded and the 2024 election is upon us, whether we like it or not. Like Jackson, Trump stands to “win” a presidential election three times – but only time will tell if the corrupt bargainers of our day will have no choice but to let him back in.

1824

President James Monroe is finishing his second term as fifth president of the United States. The Era of Good Feelings has now passed, and the unraveling period is not far away. Every president of the young republic has been a Virginia planter, except for the second, the Massachusetts statesman John Adams.

Not even forty years have elapsed since the ratification of the Constitution and the establishment of the presidency, and political fatigue has set in. The working man (the forgotten man) perceives his needs coming in behind those of the emerging bureaucracy and the political elite (sound familiar?). Andrew Jackson, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans, carries the sentiment of the working man into a four-man race for the open presidency, against establishment favorite John Quincy Adams, son of the second president, and statesmen William Crawford and Henry Clay, the latter of whom ran unsuccessfully for president three times.

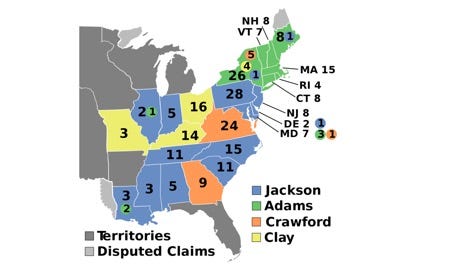

As the dust of the 1824 election initially settled, Jackson had won not only the most popular votes and carried the most states (11, with 2 elector slates appointed by state legislatures), but also tallied the most electoral votes:

Jackson 41.4%, 99 electoral votes

Adams 30.9%, 84 electoral votes

Crawford 11.2%, 41 electoral votes

Clay 13.0%, 37 electoral votes

Since no candidate achieved an electoral majority, the U.S. House took up the task of electing the next president in keeping with the 12th Amendment. Clay was dropped from consideration, leaving Adams, Jackson, and Crawford in the House’s contingent election, held on February 9, 1825. Each of the 24 states’ congressional delegations were given one vote each.

Jackson, having won not only the popular vote, but the most electoral votes, expected the House to choose him as the winner and thereby confirm the choice of the electorate. However, the Kentuckian Clay, a shrewd political operator, or career politician, persuaded delegates of the three states he carried (Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri) to throw their support behind Adams, while three delegations from Jackson-won states (Maryland, Illinois, and Louisiana) did the same.

John Quincy Adams was elected on the first ballot with the support of 13 state delegations, compared to 7 for Jackson, and 4 for Crawford. Jackson was stunned by the result, and upon learning of Clay’s inside dealings, referred to him as the “Judas of the West.” Does that sound familiar when it comes to electoral wheeling and dealing, and political betrayal?

Clay later went on to accept Adams’s offer to become Secretary of State, all but confirming that he circumvented the will of the electorate from behind the scenes. Jackson declined Adams’s offer for the position of Secretary of War, turning down an olive branch and embarking upon his 1828 campaign immediately by running against the “corrupt bargain” struck by Clay and Adams.

1828

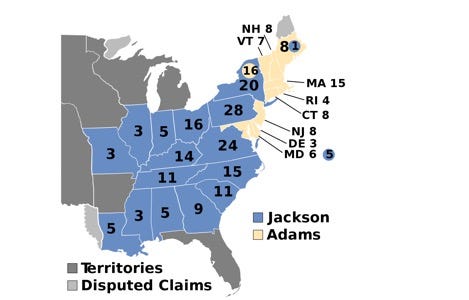

If the modern mainstream media were around in 1828, they’d have screamed various catch phrases like “Jackson can’t win if he talks about stolen elections.” Like almost everything they opine on today, they would have also been wrong way back then. In 1828, Jackson’s truth campaign paid off:

Jackson 55.5%, 178 electoral votes

Adams 44.0%, 83 electoral votes

Jackson, at long last, had his fool-proof electoral majority. While New England, much like today, still gave too much of a damn what everyone else thought, Adams became the second one-term president in American history, joining his father in that dubious category. Jackson’s campaign kicked up such a storm, winning nearly everywhere else, that it ushered in a new era of political engagement, nearly tripling the national popular vote between 1824 and 1828, when our states didn’t have the sophisticated ballot marking devices, scanners, tabulators, electronic pollbooks, registration databases, and fraudulent registrations to do it artificially.

Hard feelings were present between the sixth and seventh presidents, with Jackson refusing to bid Adams farewell after many in the outgoing president’s camp had slandered Jackson’s wife, Rachel, who died between the 1828 election and Jackson’s inauguration. Adams, in turn, did not attend Jackson’s inauguration, just like the senior Adams declined to attend Jefferson’s in 1801.

2024

Donald Trump has not yet bent the knee and come to the electorate timid to mention the issue of the corrupt bargain of 2020, the fraudulent election that ushered in another career politician to the highest office in the free world – one who didn’t campaign, but set popular vote records shattering Barack Obama’s numbers from a record setting 2008 campaign, and surpassing even Trump’s concurrent records from the same election. Few others, with Arizona’s Kari Lake being a notable exception, have had the courage to hold the line on demanding the American people have free, fair, transparent, and trustworthy elections, recalling one of the great quotes attributed to Jackson:

One man with courage makes a majority.

I have pointed out the fallacy in anyone running for office and not mentioning the crisis present in our filthy system of elections, let alone candidates for our highest office. From that article:

The reason candidates like President Trump or Kari Lake have been “losing” lately is because those seeking to preserve the current order, that of a global bureaucracy hellbent on keeping the world engaged in endless wars, realigning the global economy via corrupt trade agreements, and pitting citizens against one another by instigating racial, cultural, and social strife of various kinds have perfected election manipulation.

Team DeSantis, and all other Republican presidential campaign teams except for Trump’s, are trying to sell horses and buggies in the age of the muscle car. They are selling outhouses in the age of indoor plumbing. They are selling solutions that are not pertinent in the day and age in which we must demand restoration of a free and fair system of elections. Trump knows he must channel his inner Jackson and remind people of the latest corrupt bargain if he is to have even the slightest chance of exposing the truth and returning himself to office. The best officers, like Jackson, go to the sound of the guns, and those guns are telling us we have no future in self-government if we do not control our system of electing our representation.

I was born for a storm, and a calm does not suit me.

Andrew Jackson

“I was born for a storm, and a calm does not suit me.” - Andrew Jackson

We all need to be Jackson

We are gradually winning the narrative war through alternative media, which means the only remaining foundation for Deep State power is fraudulent elections and the brute force of corrupt institutions. It's now a race to see if we become Venezuela where everyone knows the elections are fake but it doesn't matter anymore, or, we reach enough of an awareness of the election fraud among the general public to force change. I am shocked and disappointed with some people who have switched allegiance from Trump to Desantis, who as far as I know, is not talking about voter fraud. These same people are saying other issues are more important than achieving secure elections. But in order to know which issue is most important we only need to observe which candidates the MSM attacks the most vociferously. It is those like Trump and Lake who are taking on election fraud head on.